By G. T. Antell

Nomenclature systems for researchers and study taxa

Fights between academic scientists are bitter, but only because the stakes are low. This petty politics is so infamous as to have its own name, Sayre’s Law, which theorizes that the intensity of feelings about an issue are inversely related to its importance. However, there is one common area of dispute in science that has wide-reaching importance: names, whether referring to scientists or their study subjects.

In the market of published articles, names are currency. Clashes flare among collaborators over the order of names in authorship lists. Journals have been known to turn away submitted manuscripts that fail to adhere to the letter—to the comma—of the journal’s proprietary bibliography style for naming authors, titles, and publishers in citations. After articles are published, counts of name citations are fodder to quantify and rank scholars’ achievements; these metrics can feed into hiring and promotion criteria.

Biologists take the business of naming to further extremes. Every organism formally described in Western science is baptized with a suite of names, to denote a unique signifier and define membership in wider biological groups (e.g., sapiens and Homo). The naming classification of biological groups is messy in both theory and practice, but most commonly, scientists describe a species within the nested groups of genus, family, order, class, phylum, and kingdom. In the format of a research paper, this proposed genealogy list is centered down the page, and each name is cited by the author and year of naming. For example, when I discovered a new species of fossil insect while working a student job at a natural history museum, the birth certificate I published looked something like this:

Insecta Linnæus, 1758

Strepsiptera Kirby, 1813

Myrmecolacidae Saunders, 1872

Caenocholax Pierce, 1909

Caenocholax palusaxus Antell and Kathirithamby, sp. nov.

This list tells other specialists that I and my coauthor (Antell and Kathirithamby) are describing a new species (species novus) named palusaxus, which belongs to genus Caenocholax (named by Pierce in 1909), which belongs to family Myrmecolacidae (named by Saunders in 1872), which belongs to order Strepsiptera (named by Kirby in 1813), which belongs to class Insecta (named by Linnæus all the way back in 1758). Scientists don’t bother listing the kingdom, phylum, and sometimes class because the affiliations are well-known; in this case, insects belong to phylum Arthropoda, a major group of kingdom Animalia. (Three out of four animals are insects!)

The name palusaxus is a combination of the Latin word for rock, saxum, and marsh, palus. I wanted the name to highlight that this was the first time anyone had found a fossil Strepsiptera preserved in rock, not amber—a novel condition enabled by the lagoonal environment where this gnat-like insect died. My friends were less awestruck by the majesty of a smeared dot on a chip of shale, however, and endlessly taunted me about my “swamp rock”.

Photo credit: Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

My colleagues in paleontology have named fossils for everything from Australia’s Qantas Airways (Qantassaurus Rich and Vickers-Rich 1999) to Barack Obama (Obamus coronatus Droser 2020). In fact, there are more than a dozen animals included in Wikipedia’s list of things named after Obama, making him the most popular president for eponymous scientific names to date.

Look back again at the list above and notice the oldest name, at top, attributed to the author Linnæus. Carolus Linnæus named the formal category for insects in the same treatise that named kingdom Animalia: the 10th edition of Systema Naturæ, the book credited with largely inventing the modern system of nomenclature (the rules of assigning names to organisms). For instance, the book codified the two-part format of names that we italicize as genus and species. Carolus wasn’t born Carolus; he changed his own name into Latin when writing down new names for all the other animals he knew. I, too, am a biology nerd who changed my name to sprinkle in some Latin—perhaps the only commonality I’m proud to share with Linnæus, whose heinous contributions to race science rival even the Systema Naturæ in lasting impact.

Deadnames and nomina rejicienda

The field of nomenclature has moved on apace since 1758, and there are now multiple, encyclopedic rulebooks. For animals, current regulations span 18 chapters in a fourth-edition tome maintained by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). Analogously, there is an International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN), not to be confused with the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP) or the International Code of Phytosociological Nomenclature (ICPN), which governs plant community associations. Each of these codes offers an abundance of Latin terms to denote the (in)validity of names and their origins.

One reason for the complexity of nomenclatural codes is to issue rulings for name changes, which occur frequently and for varied reasons. Oftentimes, new understandings of evolutionary history invalidate earlier ideas about the group to which a species belongs; this can justify updates to some or all of the corresponding names. The giant fossil python Montypythonoides lost its unique genus name (regretfully, according to the scientist who renamed it) after new specimens revealed it to be more likely a member of the existing genus Morelia, for example.

Another type of revision is required when different researchers independently name the same organism without knowledge of each other’s work. Occasionally, a single person even double-names something—for instance, Linnæus gave two different names to the snowy owl in the Systema Naturæ (Strix scandiaca and Strix noctua). Once a conflict like this is discovered, the rulebook dictates which name takes exclusive precedence.

Multiple names for the same organism are called synonyms, and these names have unequal statuses: unlike synonyms in thesauruses, only one word in a synonym set in biology is considered correct to use. The older one is the senior synonym, and by default it takes priority as the preferred name over newer (junior) synonyms. When names are the same age, like the two species names for snowy owl published in the same book, the first name to be mentioned again in a publication should take seniority. However, there are occasions when naming commissions deem it acceptable to reject an older name (marked nomen rejiciendum).

Scientists can call for a reversal of precedence to justify a junior name as correct instead of an older one. Article 23.9 of the ICZN lists an assortment of circumstances where this rule-breaking is acceptable. For instance, if a junior name is widely published and the original name hasn’t been used since 1899, the senior name can be rejected as a nomen oblitum, a forgotten name. Megalosaurus, the first name for a non-avian dinosaur considered valid, has a fossil specimen with an older name that is a nomen oblitum: Scrotum humanum.

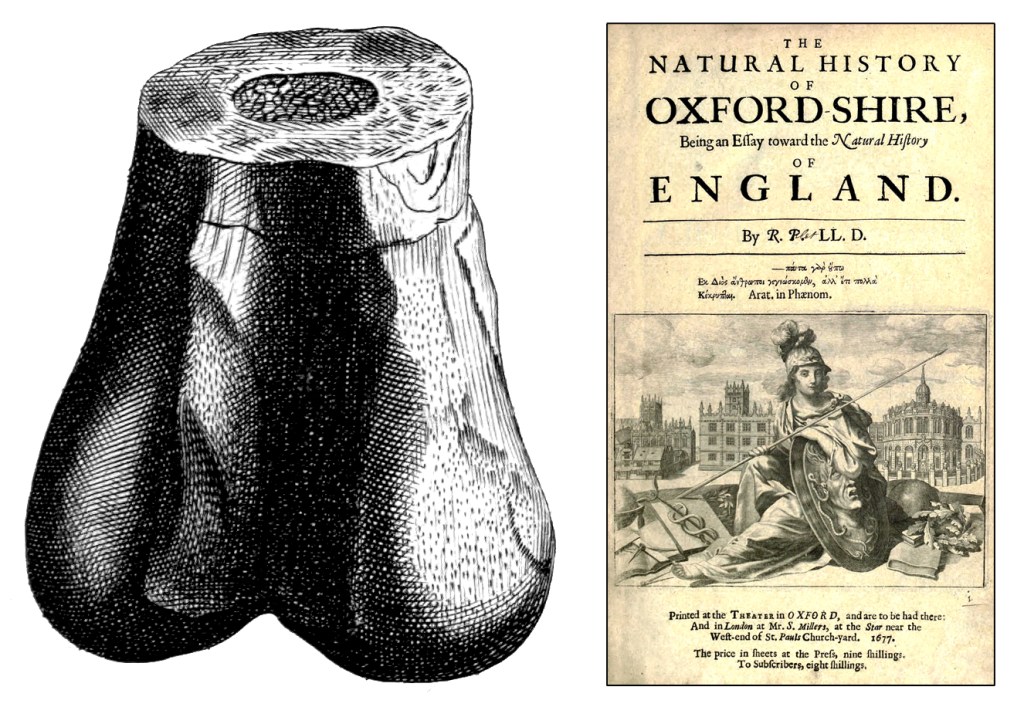

Oxford professor Robert Plot first published the fractured end of a Megalosaurus femur as the thigh bone of a Roman war elephant and then as the fossil testicles of a biblically giant human. Plot’s engraving is the first known illustration of a dinosaur fossil, and it was the basis for author Richard Brookes to coin the name Scrotum humanum. The ICZN decided it was unnecessary even to petition for Scrotum humanum to be overturned as a nomen oblitum; the original application of the name was considered so unserious it was inadmissible. Megalosaurus remains Megalosaurus.

Image credit: Robert Plot (1640–1696), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Another category of rejected names is nomina periculosa, names that could endanger health or life if used. This type of rejection is important in microbiology, where hazardous pathogens could be mishandled if relabeled in laboratories under older, unknown names. For instance, the Judicial Commission of the International Committee on Systematic Bacteriology ruled the name Yersinia pseudotuberculosis subsp. pestis should be rejected, even though it had priority, because changing the name of the bacterium responsible for the Black Plague “could have serious consequences for human welfare and health” (opinion 60, 1985).

In trans*, nonbinary, and gender-expansive communities, the sole governing authority over a name is not any international organization or government, but rather the person whose name is in question. The technical term for a senior synonym is a deadname or birth name, while junior synonyms are called chosen names or lived names. By default, priority is always given to the most recent chosen name, as deadnames are dangerous nomina periculosa. Hearing a deadname can cause distress, and outing someone with it can risk their psychological or physical safety. Just as in Latin nomenclature, it is only appropriate to refer to a being by the name that has current priority, even when talking about that person or species from an earlier time when a different name was in use. When citing scientists who have previously published under deadnames, this can mean changing the names or initials used in a bibliography to properly credit a lived name.

Self-sovereign nomenclatural revision

My name is Gawain Tempskya Antell, and this is a junior synonym: my parents published a different binomial epithet for me earlier in life. As I have examined myself and reassessed the traits diagnostic of my higher-level group memberships, I have realized a formal taxonomic revision is warranted. My family-rank name, Antell, is retained, but I reassign genus from my matrilineal group name to Tempskya, which paleobotanists may recognize as a fossil genus of tree-ferns with a growth habitat unlike that of any other known plants.

In a quirk of fate, Tempskya is a synonym given to me as a child, decades before I expressed any interest in fossils or my future profession of paleontology. My mother, a botanist, once saw a specimen label for the Cretaceous fossil in a drawer and thought it sounded lovely. Thankfully, she never assigned this name to me with formal documentation (making it a nomen nudum, a.k.a. a nickname), or I might have avoided paleontology altogether out of sheer contrariness.

Additionally, under Article 56 of the ICN, I designate my given first name a nomen utique rejiciendum, a suppressed name to be rejected outright. Gawain, correspondingly, is a nomen conservandum, a name maintained as the valid version “to avoid disadvantageous nomenclatural changes entailed by the strict application of the rules, and especially of the principle of priority” (Art. 14.1, ICN). That is, Gawain is the correct name to be used henceforth in place of its rejected senior synonym.

Photo credit: S. Jones.

Addendum

When queerness cross-pollinates with science, both domains yield more. Queerness repositions my vantagepoint and expands my willingness to challenge paradigms in science; science gives me language to describe my queerness (and a unique middle name, to boot). Here, I am being facetious about my name change to loan the legitimacy of Latin to the oft-derided subject of chosen names. From Qantassaurus to Montypythonoides, scientific names have long been as playful or unconventional as any trans*/nonbinary chosen names, yet the former are upheld in the annals of literature while the latter are too often mocked online or on the street. These days, even an adorable public library mascot to promote reading for children cannot escape a diatribe of backlash for using they/them pronouns (on account of being an alien, not transgender). The absurdity of this misplaced ire would be easier to overlook if it weren’t supported by a prominently transphobic author whom close science colleagues still follow on social media.

I avoided claiming the name I wanted for myself for months because I so feared the ridicule it might bring me. In the end, though, the only person who has ever shamed me for my name is me. As the world becomes more multilingual, multicultural, and openly (gender)queer, rare names—whether given or chosen—stand out less every year. I wish for all nonbinary and gender-diverse scientists, in ISNBS and beyond, the same easy acceptance I’ve received under a new name.

I want my fellow scientists to update their contact lists and image of me without shifting their assessment of my research capacity or commitment. I am counting on colleagues to add one more name to the innumerable taxon lists biologists carry around in memory. For those who serve on journal editorial boards, I am asking you to create pathways for authors to change published names invisibly, comprehensively, and accessibly, in accordance with the Committee on Publication Ethics’ principles.

Because names matter in science, and they’re worth being pedantic about.